Researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University have unveiled a tiny solar device that can disinfect contaminated water in minutes.

The new device offers a fast alternative to common water-cleansing methods used in developing countries such as boiling, or by placing plastic bottles filled with water in the sun so UV rays can kill the bacteria.

While the latter is an effective form of solar cleansing, it’s generally one that can take anywhere from six to 48 hours. The Solvatten decontamination device we wrote about early this year is based on the latter concept and takes 2 – 6 hours.

This new device is even faster.

At just half the size of a postage stamp, the Stanford prototype utilises not just UV light, but visible light from the solar spectrum to trigger a reaction that releases bacteria-killing chemicals capable of removing over 99 percent of contaminants from water in just 20 minutes. Once the reaction is complete, the chemicals quickly dissipate, leaving pure water behind.

“Our device looks like a little rectangle of black glass. We just dropped it into the water and put everything under the sun, and the sun did all the work,” said Chong Liu, lead author of the team’s findings reported in the journal Nature Communications.

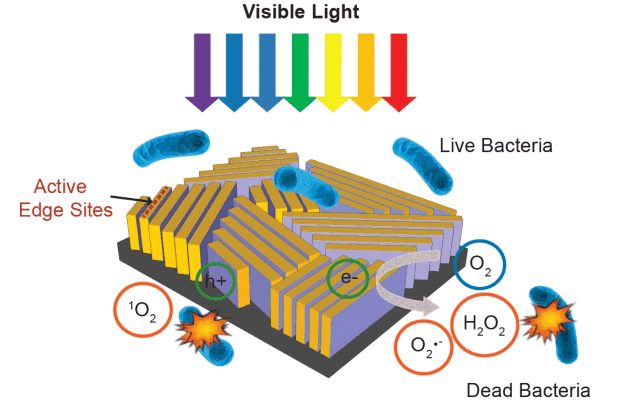

The researchers created their device by layering a tiny rectangle of glass with microscopic “nanoflake” walls of molybdenum disulphide – a compound generally used as a cheap industrial lubricant, but when deposited in films at the atomic level, transforms into a highly efficient photocatalyst. Lines of these nanoflake walls cover the surface of the device like a fingerprint, absorbing the full range of visible sunlight.

By edging each wall with the thinnest layer of copper, the scientists were able to tailor the precise chemical reactions they wanted, producing “reactive oxygen species” like hydrogen peroxide, a commonly used disinfectant, which kill bacteria in the surrounding water.

“Molybdenum disulfide is cheap and easy to make – an important consideration when making devices for widespread use in developing countries,” said Yi Cui, a SLAC/Stanford associate professor and investigator with SIMES, the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences at SLAC. “It also absorbs a much broader range of solar wavelengths than traditional photocatalysts.”

While the device successfully kills bacteria – and the team believes it would destroy viruses, too – it cannot remove chemical pollutants from water. But the team believe that their work could also have applications for the development of smog-filtration systems.

“It’s very exciting to see that by just designing a material you can achieve a good performance. It really works,” said Liu. “Our intention is to solve environmental pollution problems so people can live better.”

Another similar sort of concept we’ve covered in the past is a proposed device from Carnegie Mellon University that involves placing a rod composed of tin oxide or titanium dioxide into a bucket of water and exposing it to the sun.